In the aftermath of the devastating January fires that scorched too many parts of Los Angeles County, we think about fire’s role in our ecosystem. Fire has been part of Southern California for millions of years, but it has become more frequent in the past century due to climate change and our growing population.

Wildfires are our new reality. We are learning from scientists, researchers, firefighters and those with Traditional Ecological Knowledge about creating wildfire-resilient communities.

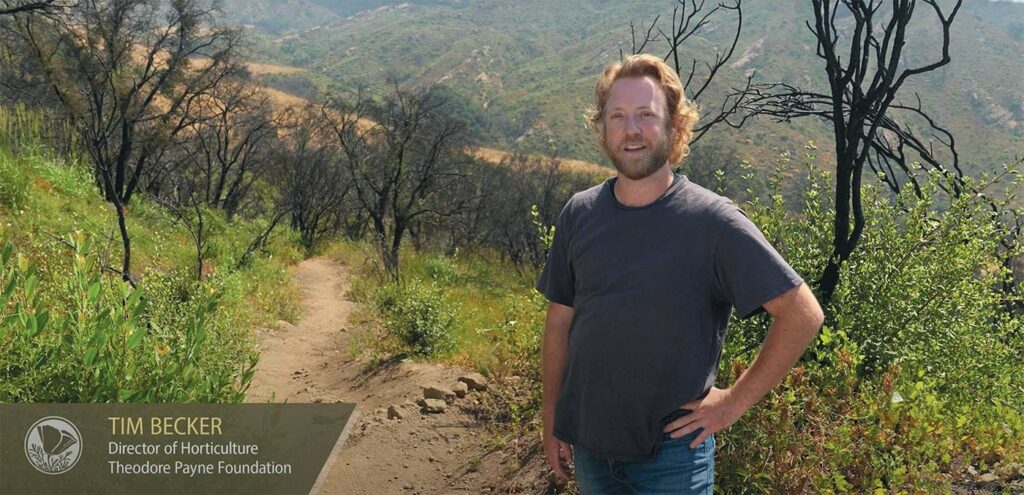

Tim Becker, director of horticulture at the Theodore Payne Foundation, walks us through why wildfires are an important part of the ecological recovery of a post-fire landscape.

We’re primarily focusing on native plants’ fire recovery. Invasive plants have their own recovery mechanisms, and when they thrive, they can heighten the area’s susceptibility to wildfires, floods and landslides. There are many invasive plants commonly seen in our area, including tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima); giant reed grass (Arundo donax); ice plant (Carpobrotus edulis); black mustard and shortpod mustard (Rhamphospermum nigrum Hirschfeldia incana, Brassica tournefortii); and periwinkle (Vinca major).

FIRE POWER

Some native plants actually need fire to germinate and to renew vegetation.

Pyrophiles are plants that need fire to open their fruit or their cone or to unlock an internal dormancy mechanism. These plants can only germinate when chemicals within the smoke from burning plant material are released. Rain then assists the process by soaking the seeds.

Fires figuratively wipe the slate clean, so you’ll see a lot of annuals immediately after a fire. These plants grow, flower, get pollinated and set seed in one year, producing copious amounts of seeds and storing them in a seed bank for one to three years. The seeds will stay dormant until a fire comes through. Chaparral mallow (Malacothamnus fasciculatus), for example, needs this scarification—abrasion from the heat—to germinate.

Other plants are obligate seeders, meaning they need fire and the chemicals in smoke to germinate. These include giant flowered phacelia (Phacelia grandiflora), wild snapdragon (Antirrhinum sps.) and fire poppy (Papaver californicum).

The woody shrub blue manzanita, or bigberry manzanita, (Arctostaphylos glauca) is an obligate seeder. When the entire plant is burned to the ground, it will not resprout. What you’ll see in a post-fire environment, however, is a lot of manzanita seedlings, particularly the bigberry and Santa Monica Mountains manzanita (Arctostaphylos glandulosa).

GOING UNDERGROUND

When a fire decimates the vegetation, plants that grow from bulbs or that have underground stems producing new plants (rhizomes) can survive due to their underground storage mechanisms.

Plants with thick rhizomatous root systems, deep enough in the ground that they don’t burn, will come back after their vegetation is cut back. Bulbs have an underground storage mechanism that completely disappears every summer, so they are secure. Other plants have a very thick woody root kind of crown, which allows them to resprout after their vegetation is gone.

Greenbark lilac (Ceanothus spinosus), toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia), oaks (Quercus sps.), chamise (Adenostoma fasciculatum) and several chaparral shrubs come back because of a lignotuber (a woody swelling of the root crown) or burl (a rounded, woody swelling on a tree trunk or base). Lignotubers are packed with starch and energy to help them produce new shoots. These plants have a massive root system, helping them to regrow quickly.

Because they still have the root system that was supporting a large 20- to 30-yearold shrub, they can grab hold of many nutrients released by the fire, such as all the potassium and phosphorus in the wood ash, and draw carbon into the soil.

Coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia) can resprout when nascent buds deep enough within the woody tissue are dormant through a fire.

ECOLOGICAL SUCCESSION

This is a process where a lot of fast-growing annuals or perennials rapidly dominate the area in the first year after a fire. That’s actually when you have the highest amount of biodiversity because you still have a lot of crown-sprouting shrubs, but you also have plants that are taking advantage of this sliver of time to dominate by reproducing and creating a huge seed bank.

You see that with annuals like the phacelia and the fire poppies, but you also see that with perennials like chaparral mallow and pink morning glory vine (Calystegia macrostegia). These two plants dominate the environment through dense growth, which provides coverage with many ecological benefits.

It prevents erosion and often protects slower-growing shrubs from herbivores and reduces sun exposure.

Underneath this vegetation, other plants will slowly make their way back to becoming the dominant species. Many of these will fade away as the larger woody shrubs come to overshadow them and out-compete them. During this time, they’re producing copious quantities of seeds and loading up their seed bank.

In Southern California chaparral systems, you would naturally see a fire every 30 to 40 years. As people encroach on wildlands and continually cause more and more fires, they are compromising plants’ abilities to regenerate because the plants aren’t able to mature and reproduce offspring.

So how can we as Californians best support the process of ecological recovery in a post-fire environment? The best approach is to do nothing; recovery will happen over time. What you can do is simply appreciate the beauty in that transition.

For more fire-related plant restoration information, visit TheodorePayneFoundation.org.

Editor’s Note: This article is courtesy of the Theodore Payne Foundation

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTOR

Theodore Payne Foundation (TPF) is a Sun Valley–based nonprofit that inspires and educates Southern Californians about the beauty and ecological benefits of California native plants. Located on 22 acres of canyon land in the San Fernando Valley, the TPF headquarters includes a full-service nursery featuring native plants, seeds, nature-themed books and merchandise, alongside display gardens, wildland hiking trails, an art gallery, educational facilities and extensive plant production areas. It offers a wide range of public classes and garden tours and has many outreach and advocacy initiatives. TPF aims to make Southern California communities more beautiful, sustainable and environmentally friendly.