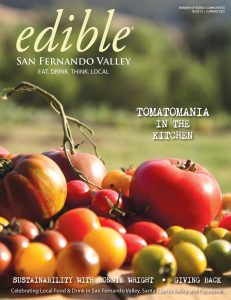

Deliciousness abounds, if you know where to look

PHOTOS BY PASCAL BAUDAR

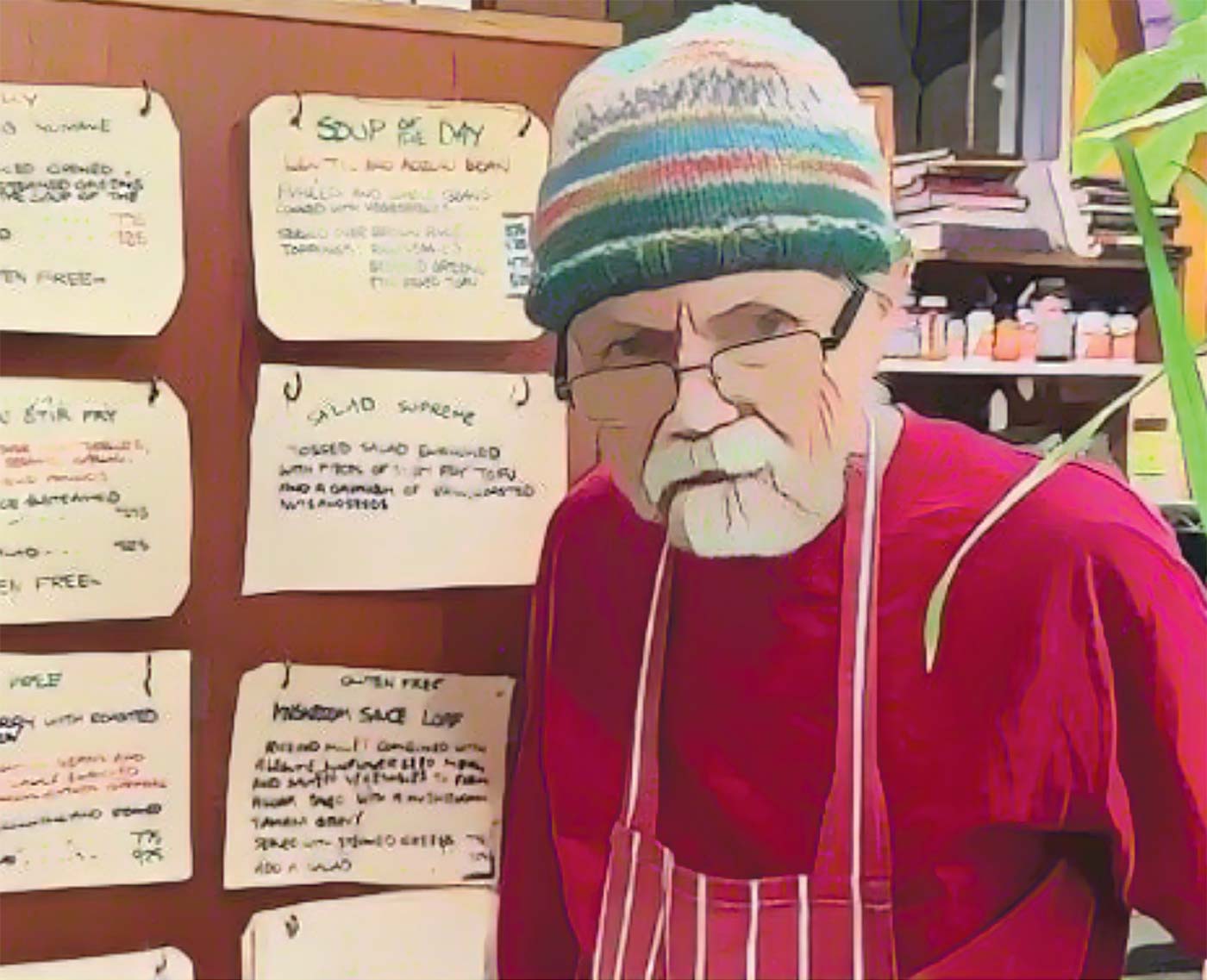

As a child growing up in a small Belgium farming town, Pascal Baudar recalls gathering dandelions with his grandmother for a family meal. He also remembers the two of them running from the property owner, who didn’t like foragers.

Baudar’s grandmother boiled those dandelions to remove the bitterness and squeezed a bit of lemon for flavor. “Simple country food,” he says, his French accent still shining through.

Like other European elders, his grandmother had an innate knowledge of wild food, because knowing what to eat, when to eat it and how best to prepare it was often a matter of survival. After the world wars devastated communities, residents who ran out of food went back to what they called the weeds, he says. “That knowledge sustained them.”

Today Bauder is a well-known advocate for simple food and wild-food culinary traditions that have sustained people for countless generations and across cultures. His determination to live on—and with—the land has gained him a following with many who want to eat well and eat extremely local.

Baudar leads classes on wild plant foraging, fermentation and food preserving, many taking place in Sylmar. His classes on food preservation are hitting at the right time: Young people are eager to learn.

“There is new attention to these methods and a reaction to all the [junk] you get in the grocery stores,” he says. “People want more natural foods and then are fed up paying $10 to $20 for a jar of store-bought ferment when they can learn how to make it for two bucks.”

For almost a decade, Bauder has written about wild food cuisine, the techniques of brewing, fermentation and crafting vinegars.

“I like to do a lot of wild food fermentation projects; it’s not cooking but it is a large part of my cuisine,” he says. “My favorite thing to do is to create delicious side dishes featuring wild foods and using traditional food preservation techniques. I also make my own vinegars, beers and wines from wild plants.”

Currently, he’s researching his next book, on edible wild seeds and grains, which will be published in 2025. “I can collect locally here in Southern California about 200 grains and seeds that are edible,” he says. “Not one of them is available at any grocery store.”

Baudar now lives in Wrightwood, where his workshop is filled with the scent of an herbal forest as he grinds, freezes and soaks seeds, leaves, mushrooms and roots. When asked about his new obsession with weeds, Baudar walks outside and plucks a familiar foxtail grass with a seed head and long, curvy, sticky barbs.

“When you go hiking, this gets into your socks and can be really painful,” he says shaking the dried brown blade. “But guess what? If you are white, this is the food of your ancestors. Look at this. When you remove the outside, you get this piece of grain that is not really interesting, but when you boil it for 15 minutes, you get this lovely red color and something delicious.” Baudar says the most common foxtail found locally is wild barley, a staple that’s been eaten for centuries.

“The thing that I really love is to find a new narrative for all those plants that nobody wants and turn them into food,” he says. “And I love doing that because that’s the ultimate survival. These plants are everywhere.”

A SECOND EDUCATION

As a young man, Baudar wanted to study foraging, but “there was no school on the subject,” he says. “So I ended up doing the next best thing, which was art. I was a graphic designer for 25 years.”

(Art is still part of his life; Baudar’s handmade bowls, dishes and plates are crafted with wild materials and local clays.)

Baudar was successful as a designer; he was also involved in the burgeoning world of virtual cities. He had companies in Pasadena, Munich and San Francisco, but with the internet fallout in the late 1990s,

he decided to return to that early love

and get a second education.

“I spent the next three years learning from different people, botanists, Native people, survivalists and environmentalists, anyone who could teach me,” he says about the 400- plus classes/workshops he attended.

Then, came the fateful year when Baudar tried to live on only wild plants, an experiment that left him often starving and hungry. “I could not get enough protein and fat,” he recalls. His epiphany: If I want to eat wild food, I need to get serious about food preservation.

Baudar enrolled in the University of California Master Food Preserver Program, and, instead of cucumbers and tomatoes, applied those traditional techniques to wild food.

He estimates he uses about 40 different food preservation techniques and he enjoys demonstrating the nutritional possibilities at our feet. “Many comment after they eat [wild food] that they feel more energetic and less tired,” he says. “They are blown away by the flavor.”

To learn about upcoming workshops with Baudar, follow him on Instagram at @pascalbaudar or visit UrbanOutdoorSkills.com. His pottery is at PascalBaudarCeramics.com.

Fire Update: We checked in with Pascal Baudar, who told us the fires wouldn’t have a great deal of impact on foraging. His greater concern was for those who lost homes and our lack of rain.

WHICH GREENS TO EAT?

ILLUSTRATIONS BY RAMIAH CHU

Pascal Baudar likes the following greens for the recipe above, but you should cook with whatever wild greens you find locally. As you experiment, keep in mind that many wild greens have strong flavors, so simple seasonings often work best.

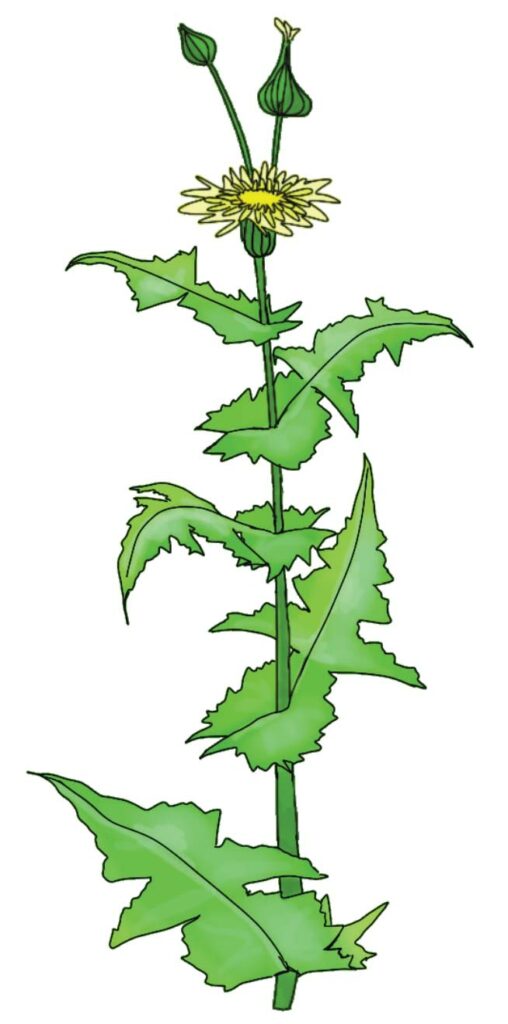

Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale):

Use the leaves. Note: Boil for 5 to 10 minutes to reduce bitterness.

Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale):

Use the leaves. Note: Boil for 5 to 10 minutes to reduce bitterness.

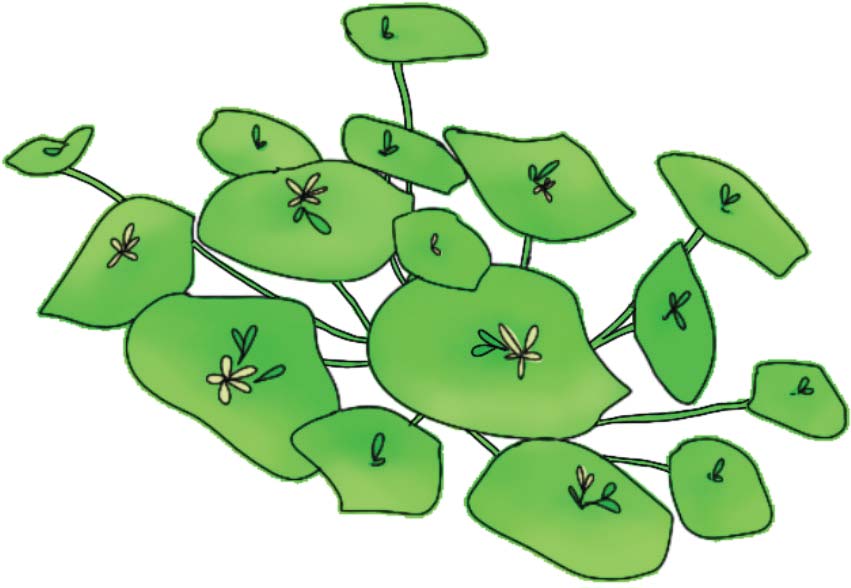

Miner’s lettuce (Claytonia perfoliata):

Use leaves and stems.

Watercress (Nasturtium officinale):

Make sure the water source is not polluted before you consume wild watercress.

Stinging nettles (Urtica urens):

Wear gloves when gathering. Boiling removes the formic acid.

Lamb’s quarters (Chenopodium album):

Use the leaves and young stems.

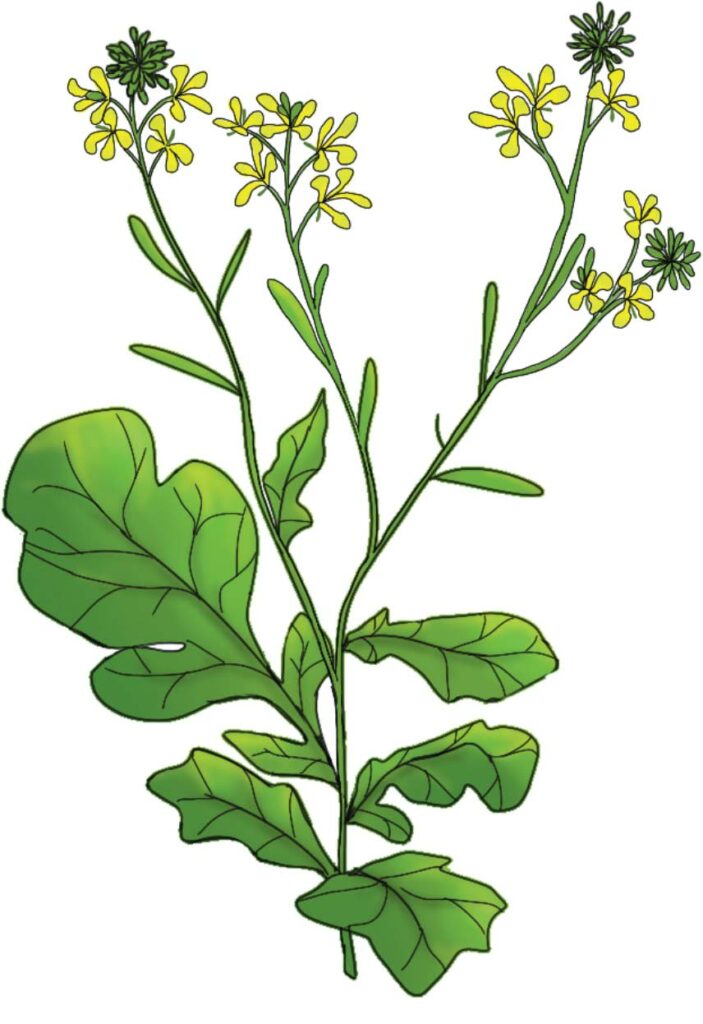

Black mustard (Brassica nigra):

Use the leaves. Note: Like many of these plants, black mustard is nonnative and invasive. When you harvest invasives, you can create a delicious meal while helping to protect the environment.

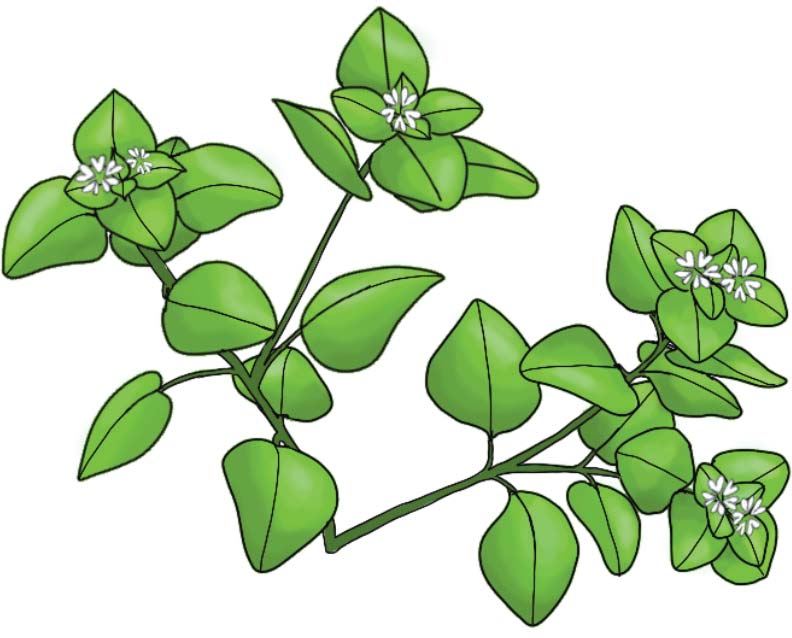

Chickweed (Stellaria media):

Use leaves, stems and seeds.

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTOR

Brenda Rees is a writer living in Eagle Rock. Originally from Minnesota, she fondly remembers how Campbell’s Cream of Mushroom soup was a kitchen staple.