Lots of pasta-bilities for artisan pasta in Pasadena

PHOTOS BY ANDREW THOMAS

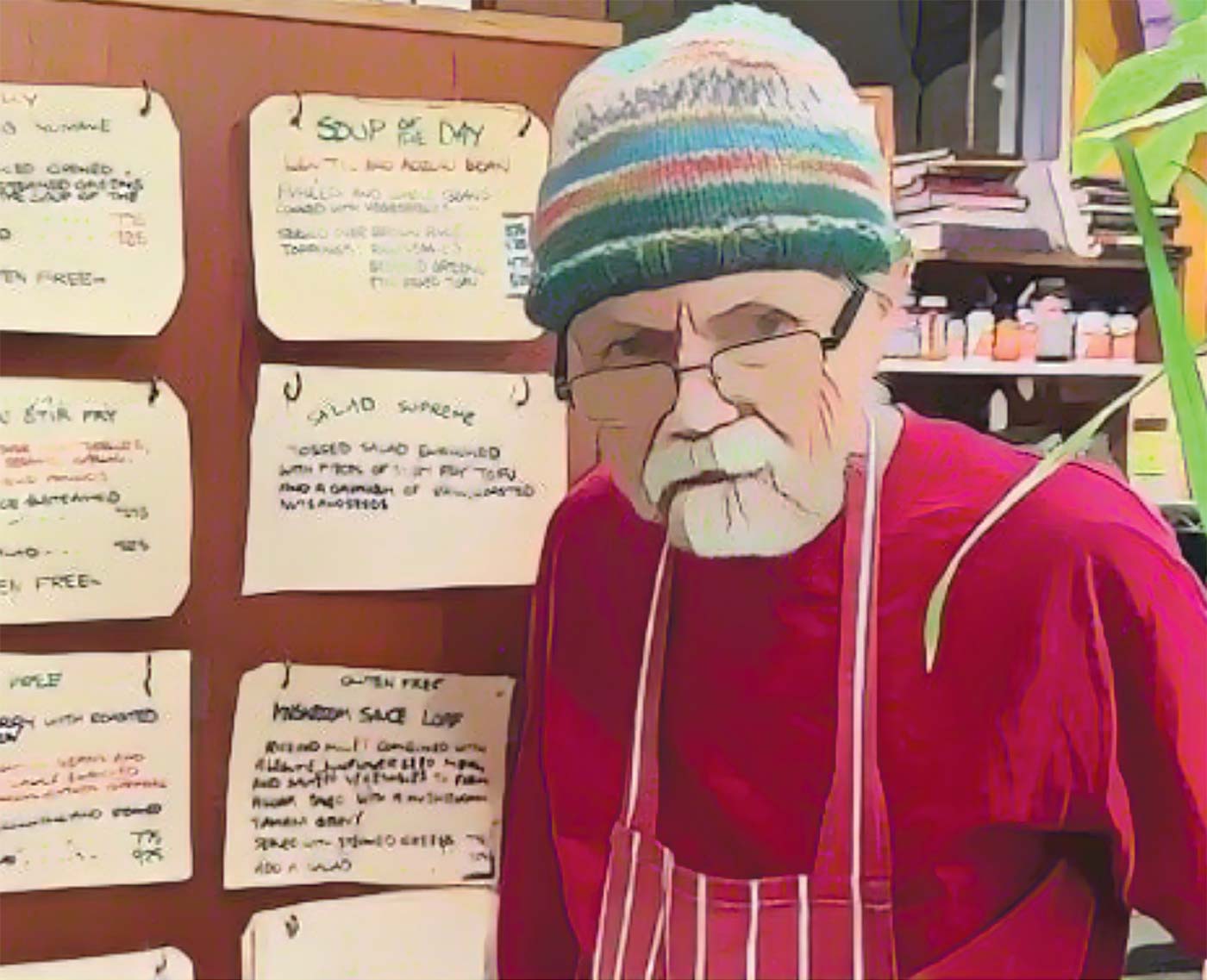

Carbs get a bad rap these days because they’re often just bland vehicles for protein, fat and flavor. But Leah Ferrazzani, founder and owner of Pasadena’s Semolina Artisanal Pasta, has a better idea.

“Most people eat [industrially made] pasta as a sauce delivery system,” she says. “But I take a lot of pride in the fact that our pasta tastes like something all by itself.” The difference lies in her choice of using certified organic semolina milled from durum wheat, and it’s the key to anything deserving of the descriptor al dente.

Most of Ferrazzani’s semolina is grown by farmers in North Dakota and Montana, then processed in St. Louis by Italgrani USA, North America’s largest durum and semolina miller. There are only three or four mills left in the country that mill certified organic true semolina, she tells me.

Ferrazzani is originally from Long Island, NY, and comes by her hospitable and nurturing vibe—the quintessence of pasta—naturally. “I come from a family of teachers and caregivers, and I think the way that expressed itself in me from a really young age was through food. … I took cake decorating classes in middle school, and I made all of my friends’ birthday cakes. I was always inviting people home to eat and, once I could, cooking for them all through college and grad school.”

Her family moved to Southern California when she was 9½ years old. She went to college in Northern California and returned again in her late 20s. An avid home cook, she’s passionate about seasonality and eating locally. Ferrazzani attributes this mindset to her college years in Sonoma County.

“Our slow production methodology focuses on flavor and texture. Industrial pasta is dried quickly at high temperatures, which destroys the volatile organic compounds that give the pasta its aroma and flavor. We dry slowly and at low temperatures.” —Leah Ferrazzani

She worked in restaurants—managing Pizzeria Mozza when it first opened—and as a food and wine writer. While on maternity leave, she became frustrated at not being able to find locally made dried pasta.

“So one day I came downstairs and looked at my husband and told him that I wanted to start a dried pasta company. He laughed and asked if I knew how to make dried pasta. I told him ‘No,’ and he said, ‘You should do that.’ So I did.’”

She has now been in business for nine years and at her Lincoln Avenue location for five.

“I taught myself how to make and dry pasta—piecing together information from scholarly articles, reaching out to cereal scientists and through lots of trial and error,” she says. “I traveled to Italy [to learn], and recorded data in the pastaficio [pasta factory] where I worked,” she says, explaining that she did so because the staff wasn’t able to tell her what was happening inside the dryer.

“And then I built my business starting with a homemade pasta dryer I built in my laundry room,” says Ferrazzani. For this DIY pasta dryer, she tiled the walls, ceiling and floor. A space heater was part of the system and box fans circulated the air. “I hooked up an egg incubator hygrostat to a Vick’s vaporizer and a CPU fan mounted in the window. The vaporizer came on if the humidity got too low, and the fan came on if the humidity got too high.”

With the small-batch pasta, the dough is adjusted by hand throughout the day due to changes in the environment and the semolina. “Our slow production methodology focuses on flavor and texture. Industrial pasta is dried quickly at high temperatures, which destroys the volatile organic compounds that give the pasta its aroma and flavor. We dry slowly and at low temperatures,” she says.

The super-refined nature of modern all-purpose flour is the result of an effort to end world hunger. American agricultural researcher Norman Borlaug, dubbed the “Father of the Green Revolution,” won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970 for his genetic manipulation of wheat and other food crops for disease resistance and greater productivity.

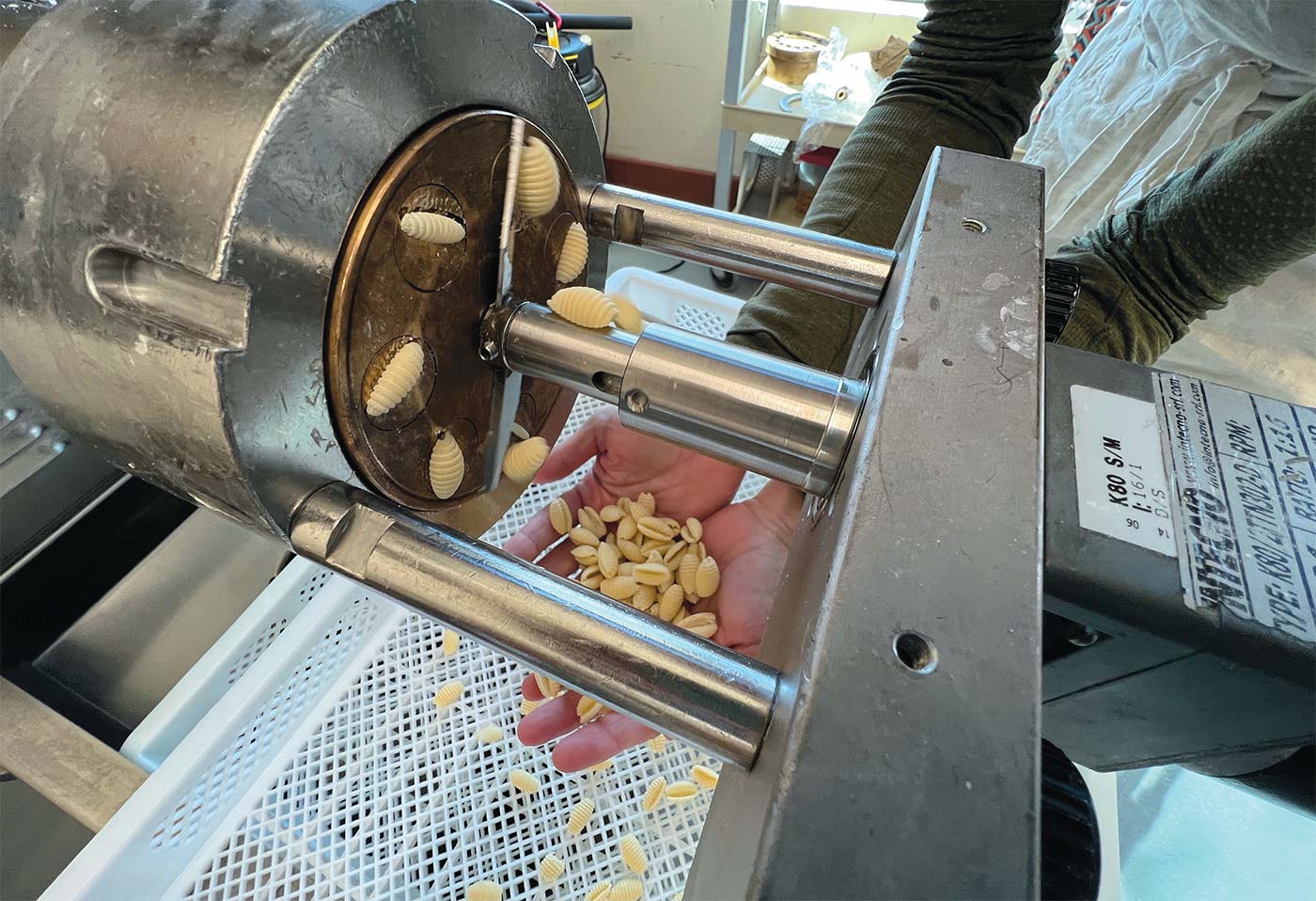

Ferrazzani optimizes the rustic nature of semolina by using an extruder fitted with bronze dies; these contribute to the rough surface texture of the pasta, which holds the sauce better.

Four days a week, the extruder yields a selection of fresh and dried pastas that are the mainstay of her storefront. Some of the dried pasta offerings include rigatoni, conchiglie (shells), conchiglie pastina (little shells), ditalini, strozzapreti and reginetti. The fresh pasta selection rotates, but there are some perennials like spaghetti and linguine, among others.

Rigatoni, strozzapreti and fusilli are among her best-sellers, finding their way to Los Angeles–area restaurants including HiPPO, Yang’s Kitchen, Little Beast, Wife and the Somm, Elf Cafe, The Cloverfield, Planta, the Fig Tree and Wax Paper, among others.

At her store, she keeps a curated selection of items to complete a meal—like heirloom beans, polline di finocchio (fennel pollen) and California olive oils)—and house-made sauces including salsa di noci (walnuts, red wine vinegar), salsa verde (arugula, anchovies, capers) and pesto Genovese (basil, pecorino Toscano, pine nuts).

If you’re hungry, get a savory made-to-order sandwich with cured meats or one of the vegetarian options. Also available are classic Italian ices, including the flavor “Blue” (raspberry-blueberry), just as it’s called in New York’s boroughs. Bada-bing!

Ferrazzani is considering expanding her line in 2024 to include egg-based pastas, which would require purchasing different equipment, and she decided to stop selling wholesale so she could “focus on the direct relationship between semolina and the people we feed.” The pasta will no longer be found at retail stores, but it’s available at the shop and online.

“I was looking to right-size the business for my values,” she says. “I didn’t want to be a national brand, which really was the next step, because making 1.5 million pounds of pasta a year isn’t an artisanal business, and that was the trajectory.”

The shop may have evolved a great deal over the last five years, but what hasn’t changed is the store’s warm and inviting personality.

“At its core, it’s still a place where my life as a home cook, my love for Italian food and stories, and my desire to connect with people over cooking all come together.”

Semolina Artisanal Pasta

1976–1978 Lincoln Ave. Pasadena

SemolinaPasta.com

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTOR

Victoria Thomas is a Southern California culture journalist with a passion for adventurous, artisanal ethnic food. Her writing explores art forms in all media, especially those she can eat