Pasadena restaurant serves up California-centric menu

PHOTOS BY TAMI CHU

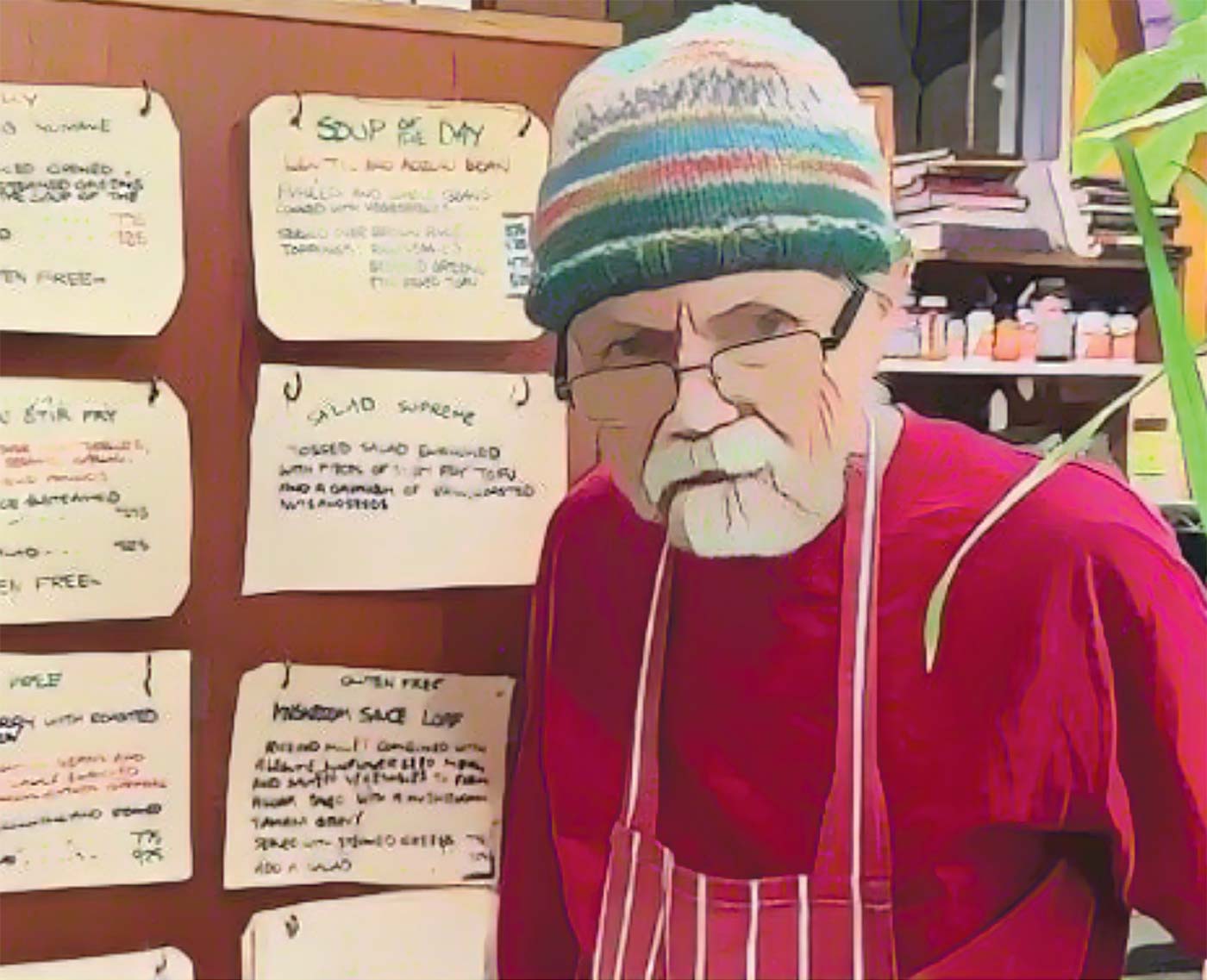

The world is changing and along with it our approach to cooking and eating. For the past seven years, Chef Ian Gresik has wielded the whisk at The Arbour, which he co-owns with his wife, Nancy. The Pasadena restaurant’s menu is shaped by locality whenever possible. “That’s great when it’s possible, except when it’s not,” he says.

He cares more, he says, about the integrity of what he serves than its ZIP Code of origin. First and foremost, “We have to support the independents, the remaining small sources who still actually forage and grow the unusual.

If we don’t, the market will shrink, and there will be fewer and fewer choices out there. As chefs, we have buying power and we drive the market, so it’s up to us to buy ethically.”

The Arbour features wild-caught proteins whenever possible, free-range chicken and grass-fed beef, and leans heavily into organic selections. The menu is abundant in regional coastal references: California Caesar salad, prickly pear jam served with warm bread pudding, soy hollandaise on seared raw yellowfin tuna, and baby bok choy dished up alongside Mediterranean sea bass.

Careful thought guides Gresik, who is pragmatic to the point of being blunt. “The pandemic changed everything, and I don’t see recovery in most areas. Boutique farmers lost their customers, and the huge grocery store chains just stepped right in to pick up the slack,” he says.

“Without demand, there’s no way to keep the complexity and diversity happening.”

In search of the increasingly rare, each week the chef sends buyers to the Wednesday morning Santa Monica Farmers’ Market, citing this iconic street happening as a holdout against industrial commoditization.

“Because the big corporate marketplace has taken over, we have to be willing to branch out. We need a wider range,” he says, explaining why not everything in his kitchen is locally cultivated. He cites chanterelle mushrooms as an example. “Now we source them from the Pacific Northwest—Washington State and Oregon—to keep it economical. We know how much our customers love them and look forward to them. But if buying from a hyperlocal source means doubling the price of the dish, we won’t do it.”

A similar reasoning defines what may be The Arbour’s most radical dish: Lobster Risotto, which supports a pound of Maine lobster meat complemented by tomatoes, beans, shallots and aged Parmesan cheese. The massively clawed East Coast lobster is generally found to be juicier and more delicately flavored than the clawless Pacific lobster (which, in scientific terms, is technically not lobster at all but is still enjoyed by many).

But that isn’t why the Maine lobster rules here. It’s because Pacific lobsters are exported en masse to China, making them substantially more expensive in the U.S. than their heftier East Coast competitors. Bottom line: The cost is less than half to schlep the crustaceans cross-country than paying for a local product with international interest.

Changes in the menu, Gresik says, often upset people. “This is a different kind of pushback to cooking seasonally,” he says. “As Americans—and especially as Californians—we are so used to having everything we want, all the time.”

He explains that his soup selections change at least four times a year, reflecting what’s just been picked. “Our proteins stay pretty constant, but we do give them seasonal nuance with how we garnish, and special sides that reflect the changes in what’s good at the moment.”

Part of the challenge, he says, is educating the customer. “We prefer not to serve Chilean sea bass or tilapia, even though they’re popular and great sellers,” he says. “They’re overfished, for one, and because of their habits, especially when they are raised in tanks.”

He’s referring to the fact that these big-mouthed bottom-feeders are often used in overcrowded fisheries to clean the water. They do this by eating fish waste, including their own.

He’s also not a fan of another favorite: broccoli, because “it’s 100% a manmade vegetable. People think of it as healthy, but we prefer to serve its wilder cousin, rapini.”

The chef welcomes shifts in the menu, whether they reflect the turn of the calendar wheel or a change in supplier. “After a few months of eating something, I get tired of it,” he says. “I am sure that our hunter-gatherer ancestors never had this problem.”

Among his current favorites are Duo of Duck with roasted breast and confit leg, parsnip purée, baby turnips, spinach and peppercorn sauce. He’s especially fond of the finish on the bird, which he describes as “more medium, versus crispy, well-done Peking duck.”

“Conscious cooking and eating is treating food as medicine. The entire process contributes to the experience. What you eat can heal you or hinder you. And who you eat with matters, too.”

The Arbour

527 S. Lake Ave.

Pasadena

TheArbourPasadena.com

FIRE UPDATE: We checked in with Chef Ian Gresik, who told us they were affected by the fires but not as much as those who lost a home or are still not back in their homes. Business dropped off during the fires and has remained slower than typical. Part of this was due to conventions being canceled, fewer tourists visiting and diners having a feeling akin to survivor guilt. The restaurant stayed open and became a place for people to grieve and tell their stories, he said.

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTOR

Victoria Thomas is a Southern California culture journalist with a passion for adventurous, artisanal ethnic food. Her writing explores art forms in all media, especially those she can eat